| |

|

(I did a bit more buckling of swashes in A Poisoned Prayer, partly because the plot just demanded it and partly because I wrote the book at least partly under the influences of Dumas the Elder and Richard Lester, the latter of whose film of The Three Musketeers is a thing of joy and wonder. Even so, I tried to be careful about fight scenes.)

|

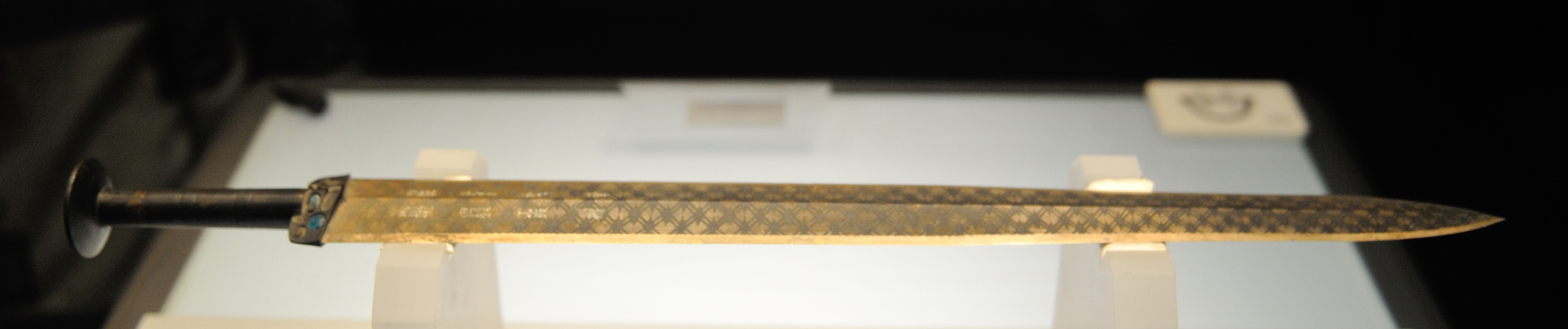

| Sword of Goujian, again, via Wikimedia |

Frankly, most pop-culture depictions of sword-fighting strike me (so to speak) as overly stylized and misleading. Much as I admit to enjoying the interminable fight at the climax of the movie version of Scaramouche (I tried reading the book; Sabatini is impossible), I sort of resent the impression it gives of the way sword-fights worked, even in the eighteenth century when they were as much ritual as earnest combat.

So I was intrigued when Do-Ming sent me a link to a scientific paper reporting on investigations of what bronze-age sword-fighting must have been like. Now, based on what has been reported (more), and on a reading of the paper itself, there likely isn't much similarity between bronze-age swordsmanship and that of feudal Japan.

But there is a single important similarity: under normal conditions, sword-fights were over quickly. None of this charismatic wounding and then fighting back to defeat the foe: if you were wounded in a sword-fight, you invariably lost. Forget eight minutes (which is how long the Scaramouche fight lasts); some sword-fights wouldn't last eight seconds. (This is something Richard Lester and his fight coordinator largely got right in the Musketeers movies.)

For an idea of what I mean, check out the fights Kurosawa put into his movies Yojimbo and Sanjuro, especially the "duel" that ends the latter movie. There's a clip of this on YouTube, which I had probably better preface with a trigger warning; first time I saw it I was, I admit, stunned.

Here is the bronze-age paper itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment