I have become, literarily speaking, an orphan.

My publisher has announced the impending closure of her press. Five Rivers Publishing is shutting down as of 1 June 2020. (My novels, A Poisoned Prayer and A Tangled Weave, seem already to have been removed from the catalogue.) This closure isn't (directly) COVID-19 related, but rather a result of family issues that will require the attention that could have been focused on publishing and books. She is absolutely doing the right thing, of course.

The response from the SF writing community in Canada has been supportive, and justifiably so: my own experiences with Lorina and Five Rivers have been marvellous from the moment of first contact. My editorial adventures with Lorina and with Robert were vastly informative and made me, I believe, a better writer now than I was at the start. I had been looking forward to working with Lorina some more, on the third novel in the French Intrigues series. And now...

... Well, what now?

The rights to A Poisoned Prayer and A Tangled Weave will revert back to me in a few days, but to be honest I've no idea what to do with them. I am not at all entrepreneurial, never have been. So the course of the determined self-publishing author just is not for me. I suppose it's remotely possible another publisher might be interested in the series, but somehow this doesn't seem too likely.

At any rate, between the shock of this news and the numbing effect of a prolonged social isolation, I won't be even attempting to do anything about this soon.

Showing posts with label Writing. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Writing. Show all posts

25 May, 2020

18 May, 2020

Fighting With Swords

| |

|

(I did a bit more buckling of swashes in A Poisoned Prayer, partly because the plot just demanded it and partly because I wrote the book at least partly under the influences of Dumas the Elder and Richard Lester, the latter of whose film of The Three Musketeers is a thing of joy and wonder. Even so, I tried to be careful about fight scenes.)

|

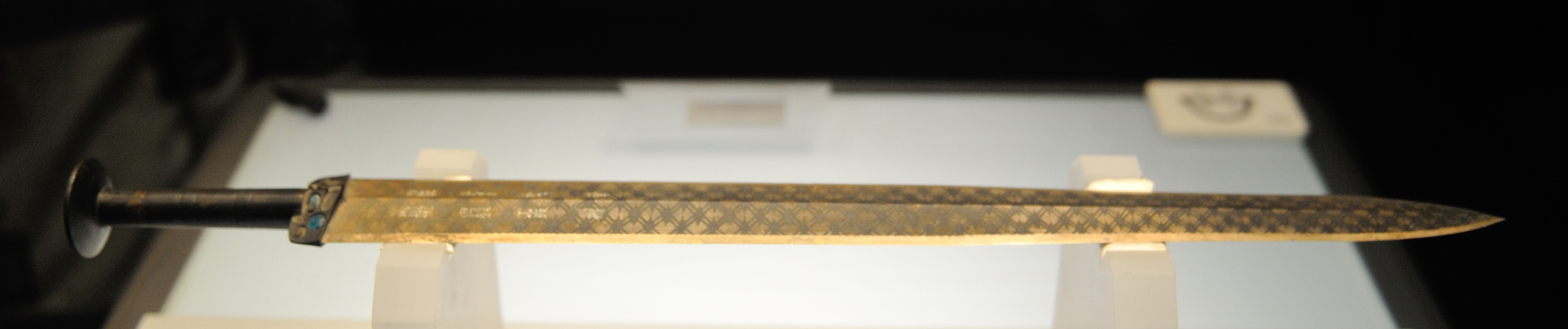

| Sword of Goujian, again, via Wikimedia |

Frankly, most pop-culture depictions of sword-fighting strike me (so to speak) as overly stylized and misleading. Much as I admit to enjoying the interminable fight at the climax of the movie version of Scaramouche (I tried reading the book; Sabatini is impossible), I sort of resent the impression it gives of the way sword-fights worked, even in the eighteenth century when they were as much ritual as earnest combat.

So I was intrigued when Do-Ming sent me a link to a scientific paper reporting on investigations of what bronze-age sword-fighting must have been like. Now, based on what has been reported (more), and on a reading of the paper itself, there likely isn't much similarity between bronze-age swordsmanship and that of feudal Japan.

But there is a single important similarity: under normal conditions, sword-fights were over quickly. None of this charismatic wounding and then fighting back to defeat the foe: if you were wounded in a sword-fight, you invariably lost. Forget eight minutes (which is how long the Scaramouche fight lasts); some sword-fights wouldn't last eight seconds. (This is something Richard Lester and his fight coordinator largely got right in the Musketeers movies.)

For an idea of what I mean, check out the fights Kurosawa put into his movies Yojimbo and Sanjuro, especially the "duel" that ends the latter movie. There's a clip of this on YouTube, which I had probably better preface with a trigger warning; first time I saw it I was, I admit, stunned.

Here is the bronze-age paper itself.

21 April, 2020

No, It DOESN'T Look Like a Crown

|

| Image ganked from Wikimedia Commons |

This week has been one of those moments. I will spare all of you the details, because honest to ghod who needs to read some more whining from a writer who can't write? But it hasn't been like me to miss a day of posting a chapter from the current serialization, and I definitely missed it Monday.

In fact, I didn't even realize I had forgotten about the task until more than twenty-four hours later.

Well, it has been that sort of experience for many if not most of us, I suspect. It has been interesting, accommodating oneself to the process of communicating with friends through video and/or audio chat services, and finding oneself forbidden from entering grocery stores or markets on account of age and alleged infirmity.

And, of course, to find oneself wondering, from time to time, when certain medical appointments and surgeries are going to be allowed to resume.

07 April, 2020

Who Feels Like Writing?

.png) |

| Image from Wikimedia Commons: Doctor Schnaubel von Rom, mid-17th century |

If it wasn't for the fact I've got several months' worth of material ready for posting (Sowing Ghosts is eighteen chapters long, meaning a dozen chapters to go and a dozen weeks of posts just requiring formatting and scheduling) this blog would certainly have fallen off a cliff by now.

I am somewhat bemused to realize that this period of isolation isn't bringing me any wonderful new discoveries. Cooking? I already do a lot of that. Hoarding? Not necessary, because we have always planned our shopping fairly thoroughly, and we tend to buy fresh meat, veg, and fruit once a week, and to buy only what we know we're going to need.

Reading? It's what I do for pleasure anyway. (This year I decided to keep track of my reading: as of the end of March I had read or reread 75 books, and I added another seven titles to the list in the first week of April.)

But I sure don't feel like writing. For me writing is my full-time job, and at the moment I don't really have the attention span to cope. I'm down to the final few scenes of the first draft of a new novel... and there's just nothing there. I can't even get myself excited about revision and rewriting.

Okay, there's nothing new in that. I can never get myself excited about revision and rewriting.

26 February, 2020

Dialogue, Not Dialect

I mentioned in an earlier post that I refuse to use dialect to differentiate a character's dialogue. Having written this I have to admit that I'm using the word dialect improperly; in my defence it's how I was taught to describe the phenomenon in question.

What I'm really talking about is a certain authorial attempt to render, in prose, the sound of a different accent. That's the word linguists use to describe the way some people pronounce a certain language—though I should add that according to Wikipedia, some linguists do use the word dialect to encompass differences in pronunciation. And sometimes what I'm talking about here encompasses both pronunciation and vocabulary (and even grammar).

The reason I refuse to use this method of writing dialogue is that I think it's insulting and offensive. To say nothing of getting in the way of the reader's comprehension.

It is perfect possible for an author to convey a character's mode of speech without having to go phonetically berserk: if I write a person saying the phrase "That's sure enough right, Master," I think I am getting across the essence of the character more effectively than if I wrote "Thas sho' nuff raht, Massa." To say nothing of treating the character in question with a bit more dignity than the alternative would.

I once received a short-story submission, for an anthology I was co-editing, that featured such aggressively phonetic a dialect-cum-speech pattern for the main characters that I was forced to reject it even though the story was otherwise a good one. (And the author has since gone on to make something of a name for themself.) I suppose this falls under the category of Personal Preference, but it's a preference I feel quite strongly about. As a rule I don't read novels that do this to their characters.*

Does anybody actually write this way anymore?

*Not that I want to keep harping on Georgette Heyer here, but she has been providing a substantial portion of my fictional calories this month. And one of the books I reread this month, The Unknown Ajax, provides an excellent example of how to use grammar and vocabulary—Yorkshire, in this case—to show a character's manner of speech without being condescending. In fact, Hugo's way of speaking plays an important role in defining his character to the reader.

What I'm really talking about is a certain authorial attempt to render, in prose, the sound of a different accent. That's the word linguists use to describe the way some people pronounce a certain language—though I should add that according to Wikipedia, some linguists do use the word dialect to encompass differences in pronunciation. And sometimes what I'm talking about here encompasses both pronunciation and vocabulary (and even grammar).

The reason I refuse to use this method of writing dialogue is that I think it's insulting and offensive. To say nothing of getting in the way of the reader's comprehension.

It is perfect possible for an author to convey a character's mode of speech without having to go phonetically berserk: if I write a person saying the phrase "That's sure enough right, Master," I think I am getting across the essence of the character more effectively than if I wrote "Thas sho' nuff raht, Massa." To say nothing of treating the character in question with a bit more dignity than the alternative would.

I once received a short-story submission, for an anthology I was co-editing, that featured such aggressively phonetic a dialect-cum-speech pattern for the main characters that I was forced to reject it even though the story was otherwise a good one. (And the author has since gone on to make something of a name for themself.) I suppose this falls under the category of Personal Preference, but it's a preference I feel quite strongly about. As a rule I don't read novels that do this to their characters.*

Does anybody actually write this way anymore?

*Not that I want to keep harping on Georgette Heyer here, but she has been providing a substantial portion of my fictional calories this month. And one of the books I reread this month, The Unknown Ajax, provides an excellent example of how to use grammar and vocabulary—Yorkshire, in this case—to show a character's manner of speech without being condescending. In fact, Hugo's way of speaking plays an important role in defining his character to the reader.

24 February, 2020

The Care and Feeding of Supporting Characters

A while back a member of SF Canada wrote a request for advice about writing dialogue, with specific reference to how to make dialogue for specific characters seem individual to them. I never got around to replying (and I doubt my opinion was missed) but it did make me think about the way I write dialogue.

And it gave me a focus for this year's Heyer Project: how did Georgette Heyer's supporting characters help the stories she told?

My reason for thinking this way is my conclusion that in fact I don't go out of my way to give my protagonists a distinctive mode of speech. Seems to me this is only going to get in the way of what these characters are in business for. Or to put it another way, how they say things doesn't matter nearly as much as what these characters say.

Where I do spend some time exploring ways of making dialogue distinctive is in the supporting characters. These individuals don't have to worry about carrying theme and plot and all those fictive parts of a balanced breakfast, so how they say things can be allowed to occasionally take prominence over what they say. So I gave Hachette, in A Tangled Weave, certain vocal mannerisms I would not have considered for Victoire. Likewise Congressman Reynolds, in The Bonny Blue Flag, has a consistent mannerism I might even call a vocal tic and Cleburne has some (possibly stereotypical) Irish sentence constructions and cadences, whereas Stuart and Patton speak in roughly similar voices.

Heyer does this as well. While I'd be hard-pressed to tell her protagonists' dialogue from one novel to the next, the supporting characters are often instantly identifiable: there is no way I'd confuse Camille d'Evron (Cotillion) from Lady Bellingham (Faro's Daughter) from Eugenia Wraxton from Lord Bromford (both in The Grand Sophy). And that's just what supporting characters ought to be like. While they might not carry as much of the plotting weight, in a comedy of manners they have to carry an exceptional amount of comedic baggage.

So it's a good thing for a supporting character to have an exaggeratedly sweet way of talk, for example, or to be prone to babbling incoherently. The writer can afford to experiment more with the dialogue and voices of supporting characters, because the dangers posed by failure are so much smaller.

One thing I will not do, however, is write in dialect. And that's a subject for another time.

And it gave me a focus for this year's Heyer Project: how did Georgette Heyer's supporting characters help the stories she told?

My reason for thinking this way is my conclusion that in fact I don't go out of my way to give my protagonists a distinctive mode of speech. Seems to me this is only going to get in the way of what these characters are in business for. Or to put it another way, how they say things doesn't matter nearly as much as what these characters say.

Where I do spend some time exploring ways of making dialogue distinctive is in the supporting characters. These individuals don't have to worry about carrying theme and plot and all those fictive parts of a balanced breakfast, so how they say things can be allowed to occasionally take prominence over what they say. So I gave Hachette, in A Tangled Weave, certain vocal mannerisms I would not have considered for Victoire. Likewise Congressman Reynolds, in The Bonny Blue Flag, has a consistent mannerism I might even call a vocal tic and Cleburne has some (possibly stereotypical) Irish sentence constructions and cadences, whereas Stuart and Patton speak in roughly similar voices.

Heyer does this as well. While I'd be hard-pressed to tell her protagonists' dialogue from one novel to the next, the supporting characters are often instantly identifiable: there is no way I'd confuse Camille d'Evron (Cotillion) from Lady Bellingham (Faro's Daughter) from Eugenia Wraxton from Lord Bromford (both in The Grand Sophy). And that's just what supporting characters ought to be like. While they might not carry as much of the plotting weight, in a comedy of manners they have to carry an exceptional amount of comedic baggage.

So it's a good thing for a supporting character to have an exaggeratedly sweet way of talk, for example, or to be prone to babbling incoherently. The writer can afford to experiment more with the dialogue and voices of supporting characters, because the dangers posed by failure are so much smaller.

One thing I will not do, however, is write in dialect. And that's a subject for another time.

17 January, 2020

Why Is This a Thing?

Further to the ongoing monologue about critics and criticism, yesterday's reading brought me this. Why in the world is this sort of stunt considered necessary?

Okay, that was a rhetorical question. I know perfectly well why it's being done. And knowing this makes me all the more happy I don't have to review movies anymore. Or, in fact, to watch them at all if I don't feel like it.

Okay, that was a rhetorical question. I know perfectly well why it's being done. And knowing this makes me all the more happy I don't have to review movies anymore. Or, in fact, to watch them at all if I don't feel like it.

05 January, 2020

Familiarity's Discontents

(Being the latest in an apparently ongoing discourse on criticism and critics.)

A few weeks ago I was talking movies with my friend Do-Ming and the discussion turned to the critical responses to Frozen 2. I haven't seen the movie myself, but I've noticed a sufficient number of reviews to lead me to mention to Do-Ming that the critics hadn't been as kindly disposed to the sequel as they'd been to the first.

Do-Ming mentioned that he'd been on the aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes* and had noticed that the critics' average was some 20 points lower than the public's average (I think it was something like 77% good for the critics, 97% for the public). What accounted for the difference, he asked. "Are critics really that picky?" One friend (RIP) argued that in fact critics were jerks who wanted non-critics to feel inferior; as I was working as a critic at the time she made this accusation I was somewhat hurt. So I prefer Do-Ming's implication, even though it's not precisely flattering either.

A few weeks ago I was talking movies with my friend Do-Ming and the discussion turned to the critical responses to Frozen 2. I haven't seen the movie myself, but I've noticed a sufficient number of reviews to lead me to mention to Do-Ming that the critics hadn't been as kindly disposed to the sequel as they'd been to the first.

Do-Ming mentioned that he'd been on the aggregator site Rotten Tomatoes* and had noticed that the critics' average was some 20 points lower than the public's average (I think it was something like 77% good for the critics, 97% for the public). What accounted for the difference, he asked. "Are critics really that picky?" One friend (RIP) argued that in fact critics were jerks who wanted non-critics to feel inferior; as I was working as a critic at the time she made this accusation I was somewhat hurt. So I prefer Do-Ming's implication, even though it's not precisely flattering either.

03 January, 2020

2020 Vision

Alert readers (both of you) will have noticed this blog has been engaged in radio silence for the past week. Well, that's about to end. After the successful (if exhausting) conclusion of a family visit and a hosted New Year's Eve party, yours truly is about to get stuck back into work again.

And for a change I might even have things to talk about that aren't serialized posts of desk-drawer novels.

And for a change I might even have things to talk about that aren't serialized posts of desk-drawer novels.

06 December, 2019

Mid-Novel Blues and Greens

I'm about fifty thousand words into the first draft of the current project. This has me between eleven and twelve chapters through a twenty-chapter outline. And, as so often seems to be the case at this point in a novel, things have slowed down (instead of two thousand words a day I'm writing more like two hundred) and my interest in the characters has begun to shrivel.

Am I concerned? I am not. This happens all the time, and I always manage to blast through and enjoy a headlong rush to the finish.

Well, nearly always.

Am I concerned? I am not. This happens all the time, and I always manage to blast through and enjoy a headlong rush to the finish.

Well, nearly always.

16 November, 2019

The Best Way To Get There

|

| Don't I wish VIA business class was like this. Dining car, Venice-Simplon Orient Express. (Simon Pielow, Wikimedia Commons.) |

My favourite way is one of the older ways: I like to take the train.

I think I owe my love of business class on VIA Rail to a couple of friends who took the train to Montreal a while back and described their trip in such glowing terms that I started looking for excuses to take the train anywhere that was more than a couple of hours away. Ottawa fit that bill perfectly.

What I love about taking the train is that it's much more comfortable than a plane, requires much less attention from me than driving, and there are things to look at while I'm sipping my tipple of choice.* The food isn't going to make anyone call up the Michelin Guide, but for my money it's better than anything you can get on a plane outside of first class. And if I want to write I can write (though writing longhand is a bit of a challenge given the way the cars move about as they progress) and if I want to read I can read.

And if I want to just look out the window there's scenery to watch that isn't clouds. In our recent train journeys we have seen foxes and bats and coyotes and the vastness that is Lake Ontario and the marvellous way leaves in this part of Canada can be silver and grey and green and orange, seemingly all at the same time.

Now I'm thinking about multi-day train journeys, in private compartments. Which reminds me of the guy I used to work with at CBC Radio, who would write scripts during cross-Canada rail journeys because confining himself to a train was the only way he could force himself to pay attention to his writing.

*Which is a Hadrian: a Caesar made with gin instead of vodka.

11 November, 2019

Practical Criticism: Making It Work For You

[Now I've got the video for that Doug and the Slugs song, "Making It Work," running through my head...]

A while back I wrote a piece about criticism, attempting to answer the question Is there still a place for this? (My answer was Yes, of course.) At that time I suggested I might have some more to say, and here it is. This is a suggestion for how you can make practical criticism work for you—which is, after all, the point of practical criticism.

I want to start by telling a story. I'll try to keep it short.

A while back I wrote a piece about criticism, attempting to answer the question Is there still a place for this? (My answer was Yes, of course.) At that time I suggested I might have some more to say, and here it is. This is a suggestion for how you can make practical criticism work for you—which is, after all, the point of practical criticism.

I want to start by telling a story. I'll try to keep it short.

04 November, 2019

A Great Equalizer?

I was trying to plot out a short story set in the world I've created for the French Intrigues novels (but set sixty or seventy years after A Poisoned Prayer) when I had one of those epiphanies that can totally derail one's creative process.

The story was to be set in Montreal and was inspired by a museum I toured during a (bitterly cold) visit a year ago. The inspiration was a display about the eighteenth-century treaty that ended some two hundred years of war between the First Nations of the St Lawrence basin, war that had drawn in the French and seriously disrupted life for all parties concerned.

It was when I was trying to figure out how magic might affect such a treaty when it suddenly occurred to me to wonder:

If there's magic in the world, is colonialism even possible?

The story was to be set in Montreal and was inspired by a museum I toured during a (bitterly cold) visit a year ago. The inspiration was a display about the eighteenth-century treaty that ended some two hundred years of war between the First Nations of the St Lawrence basin, war that had drawn in the French and seriously disrupted life for all parties concerned.

It was when I was trying to figure out how magic might affect such a treaty when it suddenly occurred to me to wonder:

If there's magic in the world, is colonialism even possible?

30 October, 2019

An Apology to Commenters

At the moment I am reading an essay on aeon entitled "Mistake" and a subtitle that begins "I think, therefore I make mistakes..." This turns out to be a cringe-inducingly accurate thing to be reading right now.

I have, from time to time, complained to friends and family that nobody has ever commented on a single one of my posts on this blog. There are about three hundred of them now... and I have only just realized that in fact there have been plenty of comments posted. I just never noticed the menu item reading Awaiting moderation. So all of those comments, some dating back many months, have just been sitting there.

Folks, I'm really sorry about this. I wasn't being rude, or at least not deliberately. I was being incredibly thick-headed. Won't happen again, I promise*.

And a hat-tip to Do-Ming Lum, whose mention of having posted a comment made me look more carefully in the first place.

*This promise not actually valid.

I have, from time to time, complained to friends and family that nobody has ever commented on a single one of my posts on this blog. There are about three hundred of them now... and I have only just realized that in fact there have been plenty of comments posted. I just never noticed the menu item reading Awaiting moderation. So all of those comments, some dating back many months, have just been sitting there.

Folks, I'm really sorry about this. I wasn't being rude, or at least not deliberately. I was being incredibly thick-headed. Won't happen again, I promise*.

And a hat-tip to Do-Ming Lum, whose mention of having posted a comment made me look more carefully in the first place.

*This promise not actually valid.

29 October, 2019

Cultural and Practical: Criticising Criticism

One of my appearances at Can*Con was on a panel entitled Criticizing Criticism. The description of same in the (online only) programming book asked: In a world of Amazon and Goodreads reviews, is there a still a need and a place for the professional critic?

The tl;dr is Yes, of course there is*.

The tl;dr is Yes, of course there is*.

17 October, 2019

The Gift of Naming

I've just abandoned my attempt to read a recently published fantasy, a pseudo-Victorian piece*. I'm not complaining about the characters or the plot; to be honest I didn't get far enough into the novel to be able to offer much in the way of an opinion on those scores.

What did for me was the names of the places (and some of the characters). With remarkable consistency these names kicked me out of the story and made me stop and wonder Why that choice? Why not something that fit better?

Lorna talks about something she calls The Gift of Naming. It's that magical talent for the mot juste—okay, the nom juste—that some writers just seem to be born with, and others develop through (I suspect) hard work. I think Sarah Monette has it; Lorna says Ursula Le Guin is the wellspring and Glen Cook an excellent possessor of the talent (she thinks it's more important in fantasy than SF, but I recall being very impressed with what I used to refer to as William Gibson's "brand-name future" as I read his Sprawl novels). And of course names are one of the things most frequently noted about Charles Dickens, though I can say without much fear of contradiction that this is a talent he was still developing when he wrote Pickwick Papers.

*No names. I'm now of the opinion that life's too short to spend time calling out, by name, authors or books I can't recommend. If I mention a book or author by name, it's because I want to recommend it.

What did for me was the names of the places (and some of the characters). With remarkable consistency these names kicked me out of the story and made me stop and wonder Why that choice? Why not something that fit better?

Lorna talks about something she calls The Gift of Naming. It's that magical talent for the mot juste—okay, the nom juste—that some writers just seem to be born with, and others develop through (I suspect) hard work. I think Sarah Monette has it; Lorna says Ursula Le Guin is the wellspring and Glen Cook an excellent possessor of the talent (she thinks it's more important in fantasy than SF, but I recall being very impressed with what I used to refer to as William Gibson's "brand-name future" as I read his Sprawl novels). And of course names are one of the things most frequently noted about Charles Dickens, though I can say without much fear of contradiction that this is a talent he was still developing when he wrote Pickwick Papers.

*No names. I'm now of the opinion that life's too short to spend time calling out, by name, authors or books I can't recommend. If I mention a book or author by name, it's because I want to recommend it.

16 October, 2019

My Can*Con Schedule

Any readers of this blog who might happen to be attending Can*Con in Ottawa this coming weekend are invited to check out the programming in which I'm participating. I've never attended this convention before but it has an excellent reputation amongst writers I know who have attended in the past. I'm looking forward to the weekend.

I'll be participating in the following:

Criticizing Criticism

Saturday 7pm, Salon D

Is there still a need and a place for the professional critic? I might have a few things to say about this: I worked as a professional critic for three decades.

Tesseracts 22 Reading, Q&A

Sunday 11am, Salon B

I'll be reading a few pages of "If There's a Goal" and then answering a few questions about how I went about researching a story set within living memory.

Hope to see (some of) you there.

15 October, 2019

Could I Do a Dickens?

.jpg) |

| Robert Seymour's first illustration of the Pickwick Club, from the first issue of the novel. Image via Wikimedia Commons. |

(Not that I would ever dare to compare myself with Charles Dickens. For one thing, by the time he was my age, Dickens had been dead for six years.)

I am not sure what I'm learning from this.

Pickwick Papers is sort of notorious for the way it rather dramatically shifted in focus after nine chapters had been written and published. Chapter Ten is when Dickens introduced the character of Sam Weller, who gradually took over the story and eclipsed a lot of the original characters, to say nothing of the original idea behind the story (which was supposed to be a series of anecdotes about comically inept sportsmen). I believe a lot of Dickens's early novels shifted about in this way, not least because the serialization format allowed Dickens to respond to the reactions of his readers.

Compare this with the way most writers work now: draft, draft, and draft again, revising and polishing and not showing the work to more than a handful of people until we think it shiny enough.

Could one serialize a novel in the way Dickens (and, possibly, other nineteenth-century writers) did? Honestly, I don't know if I would have the courage to even try it.

02 October, 2019

Read It Now: Chapter One of A Tangled Weave

My latest, A Tangled Weave, has been on the market now for two months. By generous permission of my publisher, Five Rivers, I am posting the first chapter here for your perusal.

This is the second novel in the series the Toronto Public Library has dubbed "The French Intrigues," a name I'm rather pleased with. It is not quite a sequel to A Poisoned Prayer, but it's set in the same world, involves some of the same characters, and takes place just a couple of years after the events of that first novel. (Does that make it a sequel? I still don't think so.)

Chapter One begins below the fold.

This is the second novel in the series the Toronto Public Library has dubbed "The French Intrigues," a name I'm rather pleased with. It is not quite a sequel to A Poisoned Prayer, but it's set in the same world, involves some of the same characters, and takes place just a couple of years after the events of that first novel. (Does that make it a sequel? I still don't think so.)

Chapter One begins below the fold.

23 September, 2019

Writing Racism

Yesterday I wrote about encounters with racism, for the most part what I'd call incidental, in the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century novels I read while I was waiting for my eye to heal following surgery. One of the novels I read was Kipling's Kim, and I didn't say anything about it in the previous post because it made me think about my writing more than my reading, and yesterday's post was already long enough.

Kipling is usually dismissed, these days, as a racist imperialist (or an imperialist racist, I suppose). I'm not really interested in defending him here—my own opinion probably doesn't count for much anyway, old white and male as I am, and anyway I'm not even remotely interested in trying to defend "The White Man's Burden"; oy fricking vey—but from a writing perspective there's something about Kim that jumped out at me as I read it.

Kipling is usually dismissed, these days, as a racist imperialist (or an imperialist racist, I suppose). I'm not really interested in defending him here—my own opinion probably doesn't count for much anyway, old white and male as I am, and anyway I'm not even remotely interested in trying to defend "The White Man's Burden"; oy fricking vey—but from a writing perspective there's something about Kim that jumped out at me as I read it.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)