My friend Do-Ming sent me a link this morning to a YouTube video by Adam Savage, one-time Mythbuster and all-round hoopy frood. Savage was interviewing Peter Jackson about one of the latter's many dozens of first-world-war aircraft, and the discovery Jackson (or his staff) made when they removed the fabric from the wings of the (original) SE-5a biplane.

(Note that the images in this post are not those of the machine in question. They're just pix I found in Wikimedia Commons, of museum-display aircraft.)

|

| Museum SE-5a (in what looks like a Bessonneau hanger) Image by Barry Lewis, from Wikimedia Commons |

The story thus revealed was interesting... but perhaps not quite as profound a mystery as messieurs Savage and Jackson implied.

There are two reasons for this... and I suppose I ought to summarize the "mystery" first. Briefly, it was that Jackson's team discovered a rolled-up pencil sketch tucked into what I assume was the leading edge of one of the ribs on the lower plane of the wings. The drawing was of an RFC pilot, and the big mystery was the identity of the pilot. Jackson implied that someone had removed the fabric from the wings for repair, and a person or persons unknown had slipped this drawing into the rib before the fabric was restored.

Who was the mystery pilot?

Not really much of a mystery, because the drawing turned out to be a close copy of an early-war photo of Edward "Mick" Mannock, one of the RFC/RAF's leading scout pilots of the Great War. As hundreds of YouTube commenters pointed out very rapidly.

My reason for posting this, though, is to correct what I think was a faulty impression Jackson may have given. Far from being a rare occurrence, the removal of fabric from Great War aircraft happened pretty much every time a machine was flown through combat. To understand why, you have to know a little about how these aircraft were built.

The structure of a Great War fighter was, superficially, astonishingly flimsy. The fuselage and wings were light-weight structures of wood (primarily ash and spruce, I believe), covered with linen fabric that was given some tenuous protection from the elements by multiple coats of "dope" made up of highly flammable nitrocellulose. What gave these machines their structural integrity and strength was a third component on top of wood and linen: wire.

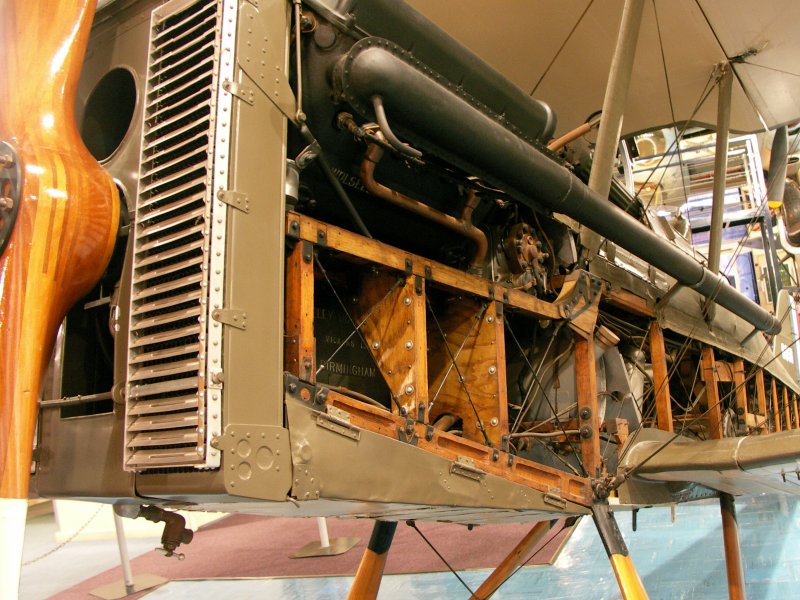

|

| An SE-5a with fuselage fabric removed (Image from South African Museum of Military Technology by way of Wikimedia Commons) |

This structure, while flexible and quite strong for its weight, was quite delicate. And the stresses of aerial combat, in which aircraft were thrown about by their pilots, were such that small (or sometimes not-so-small) changes were forced on the structure. As such, it was RFC policy that whenever a machine had been involved in combat, it had to have its basic structure trued-up again on landing. This procedure was known as "rigging," and an RFC squadron employed two different types of aircraft mechanics ("ack-emmas" in the alphabetical slang of the period): riggers to handle the structure, and fitters to handle the mechanical elements (engine, fuel tanks and supply, etc.)

So for a typical front-line SE-5a there would have been plenty of opportunities to tuck a small piece of paper into a wing rib. As for the drawing itself, my guess is that it was intended as some sort of talismanic tribute to Mannock, who was killed in combat in July 1918. (The photo from which the drawing was copied was taken in 1917 or early 1918; my guess is 1917, because Mannock's face shows little of the strain that several months of combat imposed on pilots of the period.)

Really, the true mystery of this drawing is that the SE-5a itself (or at least its wings) survived for nearly a century after the machine's manufacture. Over five thousand SE-5s and 5as were built; the survivors can be counted on the fingers of a hand or two.

(One of the big thrills of my life was seeing—and, more important, hearing—an SE-5a flying over my head as I was walking along a country road in England in 2001.)

3 comments:

Thank you for the clarification, Michael. :-) I guess one of the problems with all (or at any rate, many) modern day headlines is that they are written in a click-baity sort of way to max out the reader count. However, that is a different rant for a different day.

Quibble, my understanding is that dope was for tightening the fabric to remove wrinkles (which mess up the aerodynamics). Dope

Dope was used for a number of reasons, and yes, tautening the fabric was high on the list. If that was the only reason, though, clear dope would have been enough. Instead the RFC came up with a number of different pigmentation formulae that protected the fabric against UV radiation. I will restrain the urge to go on at length about what colour RFC/RAF aircraft presented to the observer.

Post a Comment